Brighter Days Ahead

Like so many, I am cautiously optimistic that the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is in sight. By December 2020, COVID vaccines were developed and tested. Now they are being delivered, giving us all hope.[i] However, variants of the virus may prolong the disruption to everyday lives, particularly given the hasty move to disregard federal public health recommendations in many places.[ii] COVID fatigue may be setting into the weary world, after the difficulties of 2020 and the drastic impact on our daily lives. Yet, COVID conditions have both health and economic implications which cannot be ignored.

This is the third article in my series on healthcare published in the GFMI eNews. (You can read the previous two at https://www.gfmi.com/articles/making-sense-of-healthcares-long-evolution/ and https://www.gfmi.com/articles/covid-19-lessons-for-the-economy-via-healthcare/.) The first explained the continuing evolution of the US healthcare system. The second, published early in the COVID pandemic, outlined the links between the economy and healthcare. Recent events have brought into even sharper focus the importance of continued evolution of America’s idiosyncratic healthcare system and its links to the economy at large.

By mid-March 2021, total US cases of COVID in the US was over 30 million with more than 559,000 deaths attributed to the virus.[iii] That is approaching a ten-fold increase since I wrote my last article in May 2020. A full assessment of the impact can only be made when we are on the other side of the pandemic. Yet, we can begin to see how the healthcare delivery process has changed during this period.

In this article, I look at some delivery and liquidity issues that occurred in the last year – in hospital systems and in medical practices. Together, the two have historically been responsible for more than half of healthcare expenditures. The nature and scale of government support for healthcare has changed, and that is continuing into 2021. Ideally, the health delivery methodology, business operations, reimbursement, and financing approaches can be reevaluated and amended based on lessons learned.

Cloudy Days

Since COVID hit the US shores in early 2020, our daily lives have been turned upside down. Staying healthy and avoiding the COVID virus has been a challenging mandate. Provision of care has been extremely difficult since this is a new, highly contagious virus with a range of clinical manifestations – from no symptoms to severe illness and possibly death. Additionally, prevention and treatment protocols were evolving as the disease spread.[iv]

Hospitals and healthcare systems have been overwhelmed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The high caseload, surge capacity expenses (including nurses and equipment purchases), productivity losses, and loss of more lucrative discretionary treatments and surgeries, created liquidity issues. Since COVID was a new diagnosis, it initially fell into numerous categories for treatment payments from private and government insurers. The diverse mix of payers and uninsured patients also increased bad debt levels. All combined, these caused a negative impact on liquidity and operating margins.[v]

Medical groups had an immediate patient volume decline but moved quickly to telehealth, a more flexible form of patient care that will likely endure. Initially, many practices faced a cash crunch. They sustained decreased patient volume, issues with insurance reimbursement for telehealth, and deferred elective surgeries. Medicare and other insurers soon provided necessary reimbursement changes, which offset some of this.

The impact on medical practices is varied. Some specialties have flourished (financially) because of the critical need for their specialty and government grants. Others have seen a significant volume decline because of deferred services. This could also impact hospital patient volume, as they become more available for discretionary treatments. Hospital-employed medical groups have had an advantage with their ability to increase downstream value by connecting patients to high margin services. This may further encourage independent groups to partner with a health system, payer, or other large independent group.[vi]

Past the Darkness

Operational liquidity quickly became a problem. Providers, especially hospitals and hospital systems, needed funds quickly. They faced a host of pressures that included new and additional supply acquisition at inflated prices, and labor sourced at higher rates due to the limited supply of supplemental employees. Meanwhile, lucrative discretionary procedures were being postponed, while expensive pharmaceuticals were in high demand. Cash was needed fast.

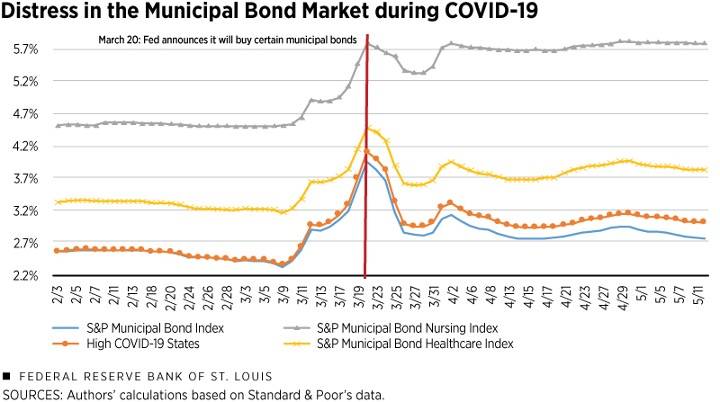

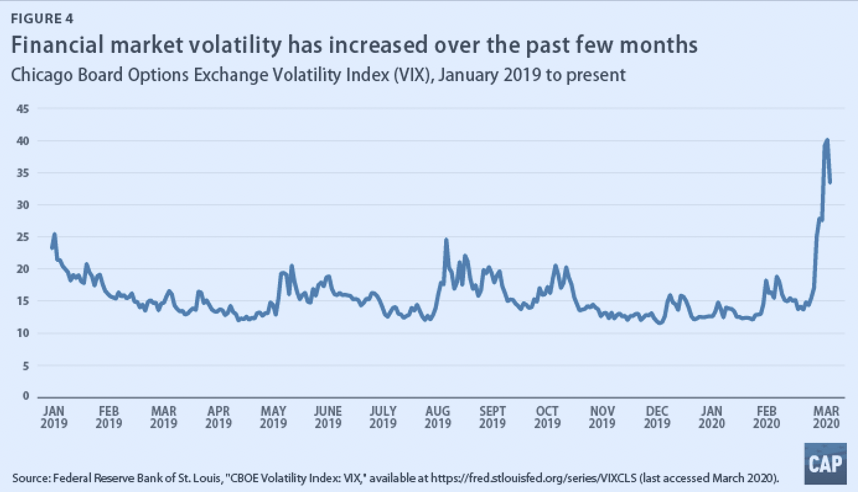

Hospital systems typically turn to their banks, municipal bonds, and investment portfolios for capital needs and liquidity. When the pandemic virus was first recognized in early 2020, the banks and financial markets entered a period of uncertainty. Market liquidity became a problem. Municipal bond funds became net sellers in March 2020, as nervous investors opted to redeem their holdings. New hospital bond issues were frozen. Banks questioned hospitals’ financial wherewithal to weather the pandemic. The stock market was volatile, so liquidating investment portfolios did not seem prudent. Market conditions were working against the normal liquidity response strategies.[vii]

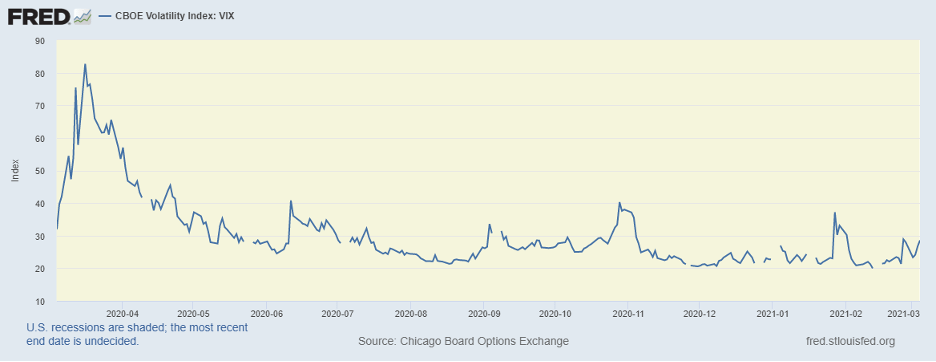

Rapid, aggressive action was desperately needed by the end of March 2020. The federal government and Federal Reserve delivered. Quick and effective responses forestalled a catastrophe in the healthcare industry.

For example, on the heels of historic legislation passed by Congress in March 2020, the Federal Reserve quickly intervened on April 9 by announcing a Municipal Liquidity Facility, which could buy newly issued municipal bonds. It had the ability to purchase up to $500 billion from eligible issuers throughout the remainder of 2020. This facility provided the needed liquidity, and most of the market returned to a level of yield above, but similar to, the sell off.[viii]

The volatile stock market argued against liquidating investment assets as providers approached an operational liquidity crisis.

Banks were concerned with their own liquidity. They also had concerns with the potentially changing credit quality of the hospital systems. The Fed intervened in March 2020, adding more than $198 billion to the financial system through repos and longer-term offerings which helped loosen the purse strings of banks.[i] The Fed’s actions stabilized the markets and gave larger healthcare system access to funds to manage their liquidity.

Conditions Today

The CARES Act Provider Relief Fund, passed by Congress at the end of March 2020, distributed $50 billion to assist healthcare providers. Hospital grants were based on total net patient revenue. Hospital revenues are a factor of volume, patient diagnosis, and reimbursement rates (which are substantially higher from private payers). This resulted in the top 10% (based on share of private insurance) receiving $44,321 per hospital bed, which was more than double the $20,710 per hospital bed for those in the lowest 10%. Those hospitals that are more reliant on Medicare and Medicaid, and with higher levels of uncompensated care, received less grant money. Larger hospitals with more market power, who command higher reimbursement rates from their private insurers, received a larger share of the grants.[i]

The new stimulus bill (passed in March 2021) follows a somewhat different path. It provides $8.5 billion in total grants, to be used for only rural healthcare providers. This will provide for healthcare-related expenses and revenues lost due to COVID-19, that are not reimbursed by other sources.[ii]

This significant government mobilization of support for the healthcare sector resulted in major hospital chains ending 2020 with massive profits. They benefited enormously from grant allocation, greater liquidity, stable payer mix, and higher acuity patients. At the opposite end of the spectrum, smaller hospital facilities, especially those in rural communities and in less affluent communities, experienced exacerbated financial instability. These facilities were also in weak positions prior to the pandemic.[i]

Grants for medical practices were also based on the same methodology – favoring those with greater revenues based on a higher percentage of private insurance.[ii] Physician groups have adapted; subsequently, telemedicine is now mainstream. Reimbursement for these services have been updated with these doctors now receiving full payment.

A New Day Dawning

While the pandemic may quite possibly end this year, its impact will be enduring and across many aspects of life. Americans have become more comfortable shopping online and working remotely. Healthcare may become one of the most impacted sectors of the economy. Telehealth visits to physicians versus office visits are likely to become common. The growth and acceptance of biopharma has been revolutionized due to the vaccine industry using mRNA, rather than live or attenuated viral forms, to create resistance to the virus.[i]

While the changes evident are already significant, the sector still has many challenges looming, which are likely to spur further evolution. President Biden’s policy for change, to date, primarily focuses on expanding the Affordable Care Act, broadening insurance availability and coverage. This is not the ideal delivery fix, but given the parameters of our healthcare delivery and political nature of changes to our healthcare system, it is realistic and achievable. He also has plans to pursue the revitalization of public health. The policy details here are less clear.[ii] In my opinion, given the current lack of focus on this critical area, this could improve our nation’s health and consequently its healthcare costs.

My article in May 2020 looked at some likely changes and additional considerations to evaluate the financial wherewithal of health care systems. At that time, my opinion was that these would be likely outcomes for 2020:

- Financial metrics will diminish.

- Expenses expected to increase substantially.

- Revenues will decrease since elective medical procedures are being delayed.

- Liquidity decreasing due to high cash outlay for increasing expenses.

- The actual impact will be determined by the amount and type of government subsidies, and the method of distribution.

As I had suggested, the actual financial impact was, and still is, determined by government intervention. Hospital subsidies were needed to keep them operational and help generate operating cash flow. Intervention by the Fed was also essential for the financial markets, providing systems with access to sources of cash.

The ultimate impact of the ongoing pandemic is uncertain. The lessons of intervention thus far offer opportunities to learn and face the challenges ahead to improve healthcare delivery and the system overall.

As Winston Churchill once said, “never let a good crisis go to waste”.[iii] Let’s learn from this crisis and make the necessary changes to align our healthcare delivery system, and to prevent and contain future healthcare crises.

About the Author: Ann Dodd

With 30+ years of financial services experience, combined with problem-solving, needs analysis, writing, and communications skills, Ann Dodd provides the expertise to plan and structure solutions to achieve measurable goals. She has a proven, consistent record of establishing mutually beneficial relationships in sales; comprehensive expertise in financial solutions and products; and exceptional leadership and management skills.

With 30+ years of financial services experience, combined with problem-solving, needs analysis, writing, and communications skills, Ann Dodd provides the expertise to plan and structure solutions to achieve measurable goals. She has a proven, consistent record of establishing mutually beneficial relationships in sales; comprehensive expertise in financial solutions and products; and exceptional leadership and management skills.

Ann has designed and facilitated learning programs in credit; pension and 403b plans, and financial management. She has also worked on the development of Basel II compliant internal grading scorecards, and has been a subject matter expert for numerous specialized industry scorecards due to their unique credit characteristics. She has led teams of credit professionals in risk assessment of loan portfolios for sale, and assisted with credit asset reviews for banks. In addition to her own consulting business, Riosca Training and Consulting, Ann has extensive financial services experience with Wells Fargo Corporation where she managed and approved credit risk for clients in both the Corporate and Investment Banking Healthcare and the Not-for-Profit Healthcare groups; Toronto Dominion Bank where she was a Senior Credit Officer in Corporate Banking; and Bankers Trust where she was trained and started her banking career.

Copyright © 2021 by Global Financial Markets Institute, Inc.

23 Maytime Ct

Jericho, NY 11753

+1 516 935 0923

www.GFMI.com

[i] www.nature.com/The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines — and what it means for other diseases

[ii] www.researchgate.net/publication/349012661/Development and deployment of COVID-19 vaccines for those most vulnerable\

[iii] coronavirus.jhu.edu 3/12/21

[iv] www.umc.edu/news/News_Articles/2020/12/Think the rules on COVID-19 keep changing? Here’s why – University of Mississippi Medical Center)

[v] https://www.advisory.com/topicstopics/covid-19/2020/05/covid-19-financial-impact

[vi] https://www.advisory.com/topicstopics/covid-19/2020/05/covid-19-financial-impact

[vii] Municipal Bonds Help Cities During COVID-19 | Morgan Stanley

[viii] www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/fourth-quarter-2020/How COVID-19 Affected the Municipal Bond Market | St. Louis Fed

[ix] www.cnbc.com/2020/03/12/Fed pumps $198 billion into short-term repo bank funding operations (cnbc.com)

[x] www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/distribution-of-cares-act-funding-among-hospitals

[xi] www.natlawreview.com/article/american-rescue-plan-act-2021-key-healthcare-provisions

[xii] www.fiercehealthcare.com/ hospitals/large-hospital-chains-post-profits-2020-thanks-to-higher-acuity-and-liquidity

[xiii] www.fiercehealthcare.com/ hospitals/large-hospital-chains-post-profits-2020-thanks-to-higher-acuity-and-liquidity

[xiv] The Next Normal: Business Trends for 2021 | McKinsey

[xv] www.forbes.com/sites/joshuacohen/2021/02/01/ bidens-healthcare-agenda-in-2021-shoring-up-the-affordable-care-act

[xvi] realbusiness.co.uk Aug 2020

Download article

My Cart

My Cart