In an April 2019 blog post, “Negative Interest Rates? – The Enigma Explored!”, GFMI examined the definition of negative interest rates, the reasons for negative interest rates, and the potential for a better option than buying a fixed income security with a negative yield. In this article we explore the current state of sovereign yield curves, share a bit of history, and provide insight and updates on some global markets where negative interest rates have penetrated.

Negative Interest Rates: Where are we now?

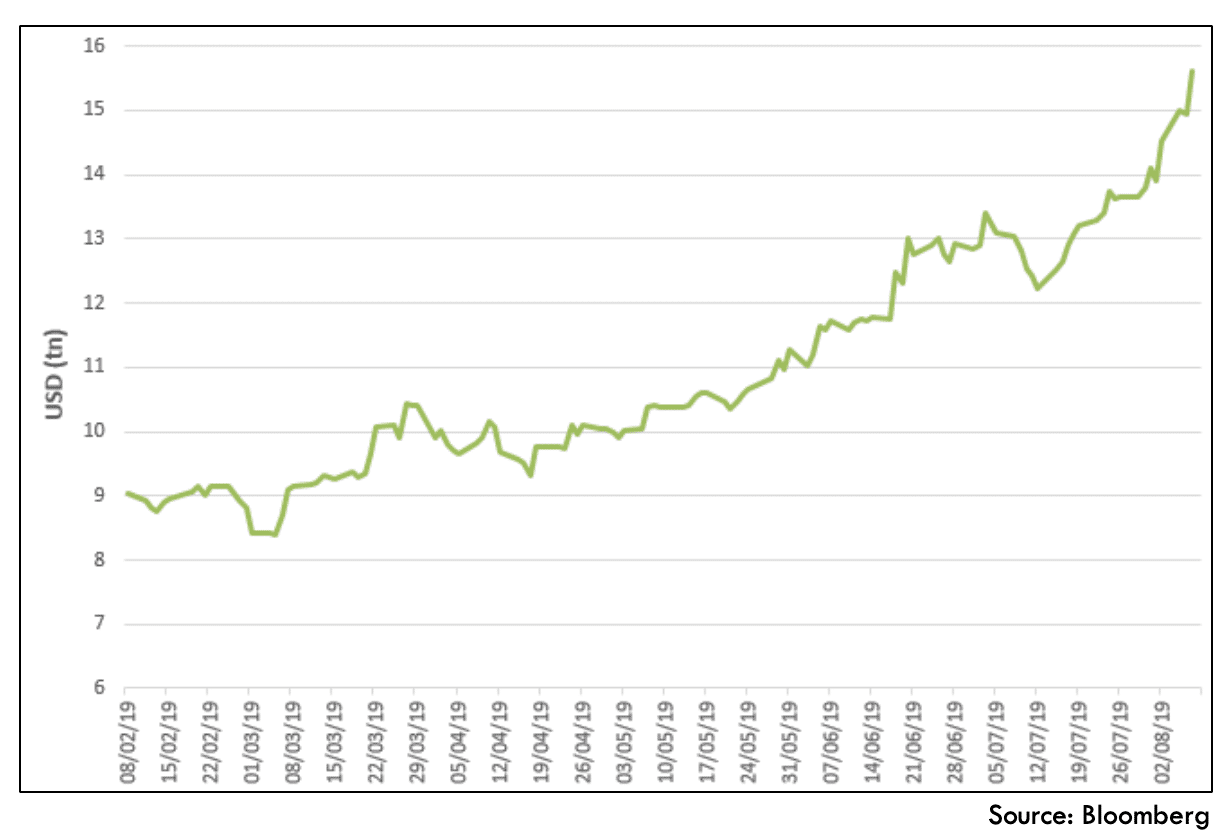

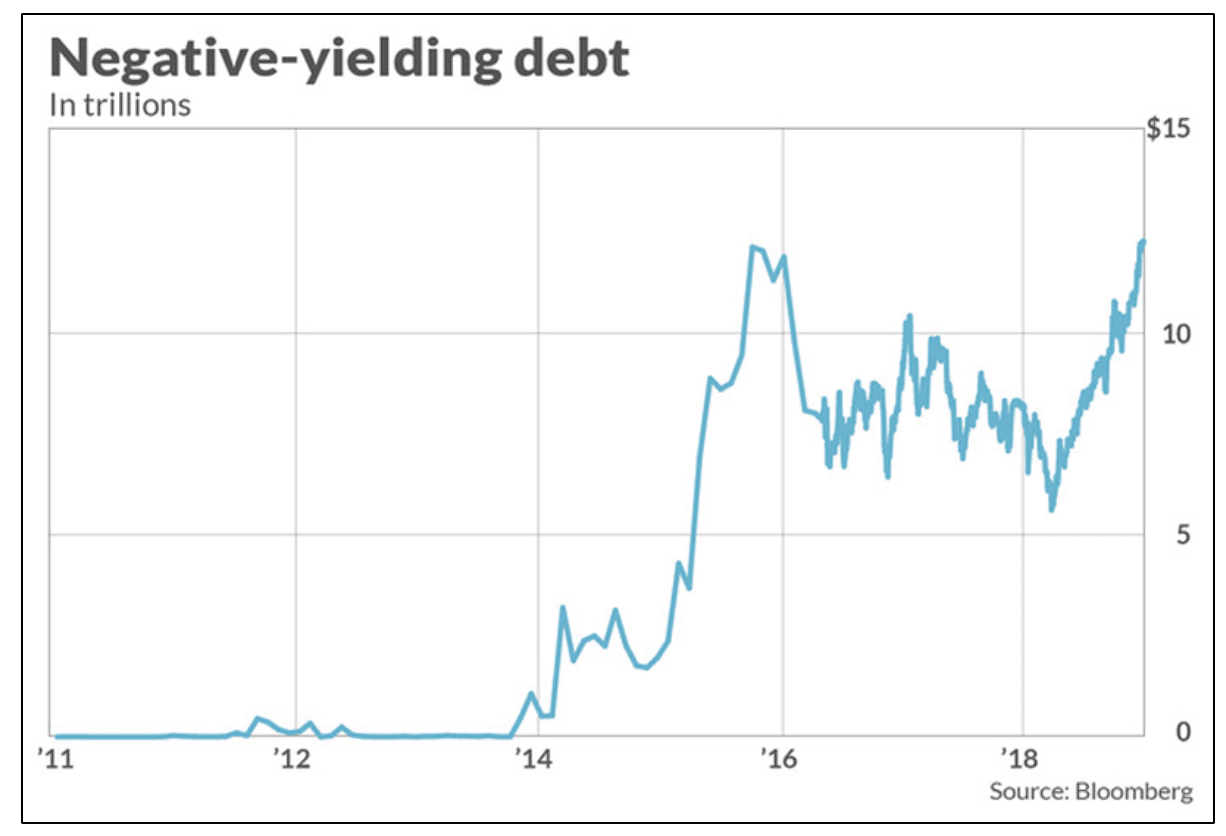

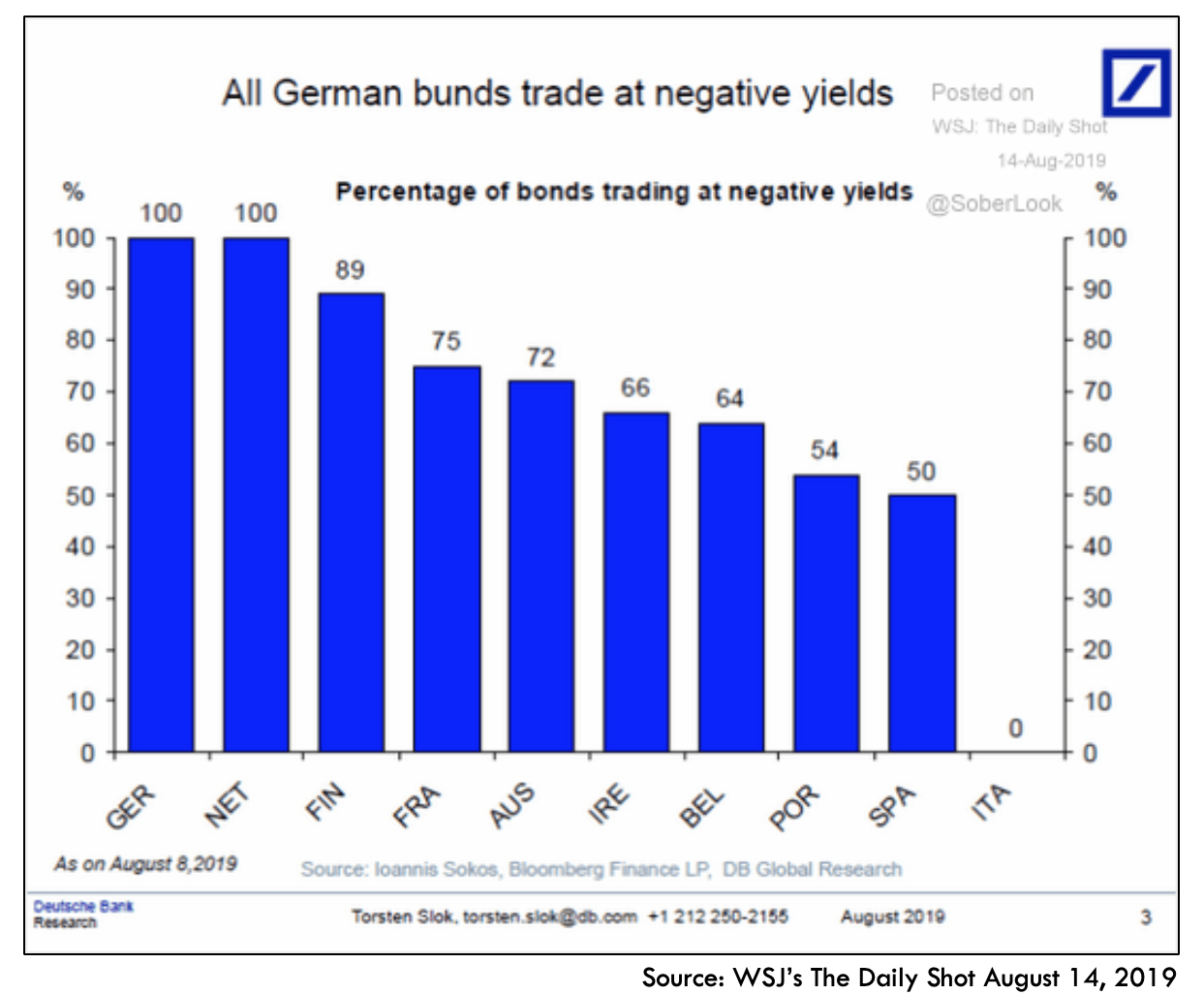

Under “normal” circumstances, when institutions such as corporations, banks and governments want to borrow money, they will often issue a bond. The investor who buys the bond receives interest in the form of a coupon for being the lender. But globally speaking, today’s interest rate environment is hardly “normal.” It is estimated as of August 2019 a full 30% of the world’s government bonds now offer investors a negative yield, meaning the lender now pays the borrower to invest in their bonds and to lend them money. A bond with a negative yield is purchased at a market price greater than the sum of future interest and principal payments. Therefore, the investor has a negative rate of return (assuming the note/bond is held to maturity), or a “negative interest rate.” This literally and figuratively means that investors are paying these governments to hold onto their money. As one can see in the following graphs, the scope of negative interest rate bonds is growing.

Graph A: Shows the value in (USD billion) of the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Negative-Yielding Debt index, which is now approaching $16 Billion USD.

Graph B: Shows the Rate of Growth of Negative Yield Sovereign Bonds.

Graph C: The percentage of each country’s debt trading with negative yields.

Negative Interest Rates: It started with Sweden

As a function of their monetary policy, central banks often adjust key interest rates. One of these rates is the Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER). This is the rate the central bank pays to member banks for keeping their excess money on deposit at the central bank. For example, the Federal Reserve now pays US banks an IOER of 2.10%. (For a brief history of the tools used to manage monetary policy in the US, go to https://www.gfmi.com/articles/the-federal-reserve-tools-past-and-present/.)

In 2009, the central bank of Sweden made the unprecedented decision to make the IOER rate negative. Essentially, they charged banks for keeping their money on deposit at the central bank. The goal of this move was to try and encourage the banks to start making more loans, to lend out their money, thereby stimulating the economy. If banks were going to be penalized for holding their money at the central bank, they would be much more willing to make loans. In 2011, the Bank of Sweden reset the IOER even lower.

In 2012, Denmark also implemented negative IOER as a monetary tool for growth.

In 2014, the European Central Bank (ECB) instituted an IOER of negative 0.10%. Much like Sweden and Denmark before them, the intended goal was to prevent the Eurozone from falling into a deflationary environment. Successive cuts have now driven that rate to a negative 0.40%. This was viewed by many as a “last ditch effort” to drive economic growth. Another reason the ECB has turned to negative IOER is to intentionally lower or devalue the value of the Euro. Low or negative yields on European debt will also serve to reduce foreign investments, thereby further weakening demand for the euro. A weaker euro should stimulate demand for exports and hopefully encourage exporting businesses to expand.

In January 2016, Japan joined the ranks of central banks charging negative IOER with a stated rate of negative 0.10% for bank reserves held at the central bank.

These central banks were responsible for the negative short-term interest rates in their markets. It was the increase in demand for government notes and bonds which resulted in negative interest rates for longer term government bonds. Due to current global economic uncertainties, the fear of recessions, and the fear of other assets losing value, there is strong demand for these government notes and bonds even at their negative yields. Additionally, there are many institutional investors such as insurance companies, pension funds, and even many mutual funds which fiduciarily must invest in bonds, regardless of the available interest rate.

Another consideration for the negative long-term rates is the impact of Quantitative Easing (QE). Essentially, these programs which were implemented by Japan, the ECB, and other countries involved the central banks creating money to enter into the market and to purchase assets such as bonds. The demand further drives up bond prices, reducing available yield in the marketplace. This maneuver also is intended to drive longer term interest rates down in order to stimulate their respective economies.

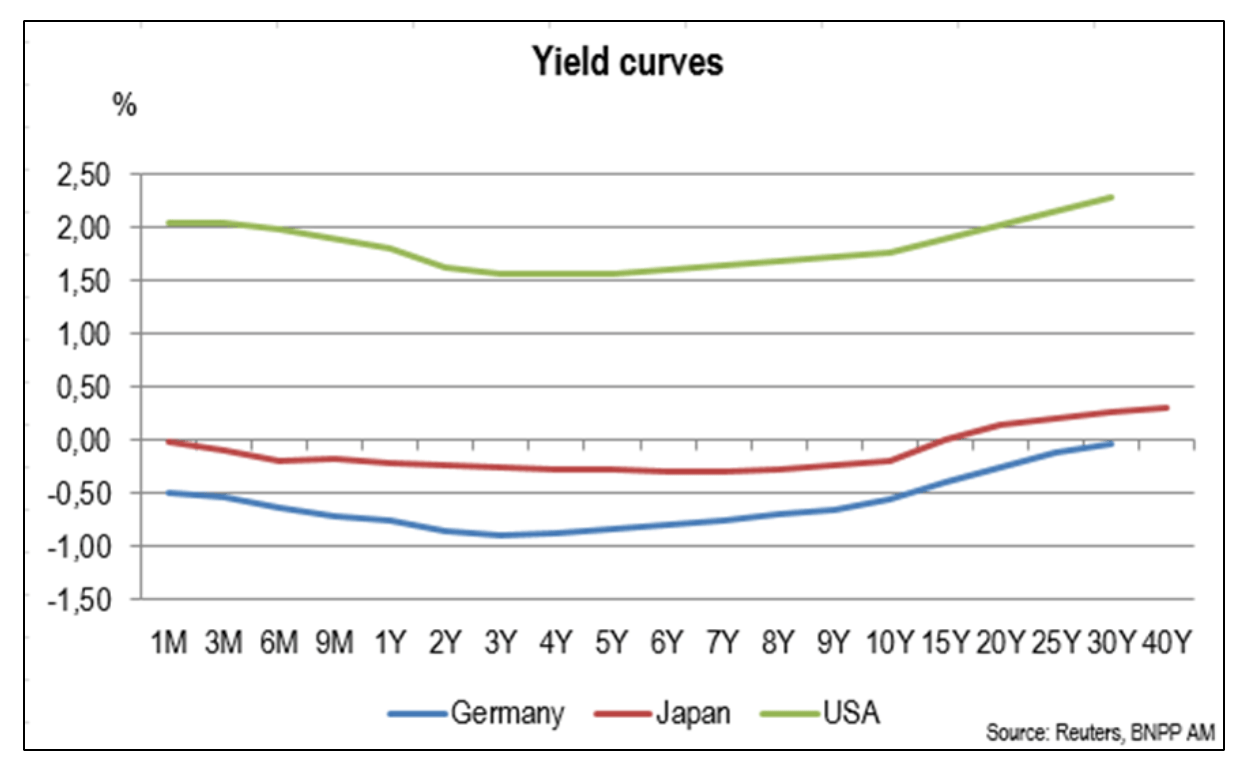

Graph D: As a result of these and other factors, the yield on many governments’ notes and bonds are now less than zero. As of August 2, 2019, the entire yield curve for Germany shows that all treasuries, from 3-month to 30-year maturities, presently trade at a negative yield. In Japan, yields available on bonds with a maturity up to 10 years are now negative, but longer-term bonds still offer a positive rate of return.

In the US market – although we are experiencing low (and lowering) interest rates and an inverted yield curve – we have not yet experienced negative interest rates, either at the central bank level or in longer maturity bonds. However, Alan Greenspan acknowledged in an interview on August 13, 2019, that “There is no barrier for US Treasury yields going below zero. Zero has no meaning, besides being a certain level.”1

Negative Rates from the Borrower’s perspective

Negative interest rates obviously benefit the borrower, and this is true for the individual borrower, as well as the corporate or sovereign borrower. For example:

Negative Yield Mortgages

In Denmark, banks recently announced they are now offering mortgages at a negative yield. The yield on a fixed rate mortgage is currently negative 0.50%. Therefore, banks will pay the borrower ½ of 1% to take their money.

Low cost to fund deficits by sovereign countries

As indicated above, 30% of global sovereign debt (estimated value at $15 trillion) is now negative yielding.2 This obviously lessens the cost of borrowing substantially by these governments. With many sovereign deficits growing, this is an important consideration.

Corporate Bonds

Corporate issuances (even some “junk” issuers) can now borrow money at negative rates: Currently, more than 20% of European investment-grade corporate debt have negative yields and during the week of August 5, 2019, we witnessed the first corporate new issuance of a negative-yielding bond. Investors will pay nearly 1% for the privilege of lending a French payments company, Worldline, €600 million ($668 million), through their recent convertible bond offering.

Negative interest rates have even spread into the high yield (“junk”) market. The value of junk bonds in the market now exceeds €3 billion. High-yield borrowers with bonds denominated in Euros trading with a negative yield include3:

- Ardagh Packaging Finance plc /Ardagh Holdings USA Inc.

- Altice Luxembourg SA

- Altice France SA

- Axalta Coating Systems LLC

- Constellium NV

- Arena Luxembourg Finance Sarl

- EC Finance Plc

- Nexi Capital SpA

- Nokia Corp.

- LSF10 Wolverine Investments SCA

- Smurfit Kappa Acquisitions ULC

- OI European Group BV

- Becton Dickinson Euro Finance Sarl

- WMG Acquisition Corp.

Negative Rates from the Lender’s (or Saver’s) perspective

Obviously, it is the lenders, or savers, who are penalized by this negative interest rate environment. Not only is the absolute level of interest often negative, many of these economies are still experiencing a certain level of inflation – meaning that their real rate of return (when adjusted for inflation) is even lower.

As we concluded in our blog post on negative interest rates: For now, it looks as though negative interest rates will remain part of the financial landscape.

References

About the Author

With over 24 years of managerial background in the financial industry, William “Bill” Addiss has been a professional designer and deliverer of custom financial learning events for 15 years. Prior to founding his own consulting service, Bill spent his first 23 years in the markets at Lehman Brothers, and its predecessor firms: Shearson and E.F. Hutton. As a Managing Director, Executive VP, Bill headed up the Fixed Income division of the firm. During his tenure there, he evolved through numerous responsibilities including National Sales Manager for Fixed Income, National Marketing Director, and Commodity Specialist. His first 4 years were in the Operations side of the business, before moving to Capital Markets front office responsibilities. As MD/EVP at Lehman, Bill managed a division of 257 professionals including Traders, and Trade Support Professionals.

With over 24 years of managerial background in the financial industry, William “Bill” Addiss has been a professional designer and deliverer of custom financial learning events for 15 years. Prior to founding his own consulting service, Bill spent his first 23 years in the markets at Lehman Brothers, and its predecessor firms: Shearson and E.F. Hutton. As a Managing Director, Executive VP, Bill headed up the Fixed Income division of the firm. During his tenure there, he evolved through numerous responsibilities including National Sales Manager for Fixed Income, National Marketing Director, and Commodity Specialist. His first 4 years were in the Operations side of the business, before moving to Capital Markets front office responsibilities. As MD/EVP at Lehman, Bill managed a division of 257 professionals including Traders, and Trade Support Professionals.

He resigned from Lehman in 1999 to establish his own consulting/training firm, which designs, develops and delivers on-site and web-based programs for various international clients in the financial industry. Utilizing his managerial and industry experience, Bill has designed and delivered engaging programs focusing on Capital Markets, Fixed Income, Derivatives and other related topics. Accordingly, he has instructed programs for a wide variety of institutional clients, including Multi-National Banks, Investment Banks, Regulatory Agencies, Rating Agencies and Asset Managers. He is known for his inter-active manner of addressing current topics and applying the course materials in a relevant way to the participants’ interests.

A speaker and lecturer as well, Bill has delivered for the Wharton/Arresty Institute and briefly served as the president of Community Securities in Rochester, NY, a regional broker dealer.

Copyright © 2019 by Global Financial Markets Institute, Inc.

PO Box 388

Jericho, NY 11753-0388

+1 516 935 0923

www.GFMI.com

Download article My Cart

My Cart