| The financial crisis exposed a number of critical weaknesses across the largest banks and highlighted that many BHCs had a limited ability to effectively identify, measure, and control their risks, and to assess their capital needs.

CCAR Review 2015, March 2015, Board of Governors, Federal Reserve |

Stress testing has been an important part of bank risk management for many years, with some form of a test used for the analysis of credit, liquidity, and market risk exposures. Given this, you might wonder why recent regulatory requirements for stress testing have proven so challenging and have resulted in adverse findings for so many banks.[1]The global financial crisis, which began in 2007, revealed numerous shortcomings in bank risk management practices; many depositories failed and government intervention was required at an unprecedented level. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (DFA) was passed by Congress in 2010 and subsequent rules were created by bank regulators to address these shortcomings and mitigate the need for costly government support in future downturns. In particular, very specific requirements for comprehensive balance sheet stress testing were established. This assisted regulators with answering the seemingly simple question: Do banks have enough capital to survive an economic downturn? If regulators conclude that the answer for a particular institution is ‘no’, that firm will be required to bolster its capital levels immediately or modify its future business plans accordingly.

It turns out that the process for producing well-substantiated answers to questions around capital adequacy is actually quite complicated and attempts to do so have revealed that traditionally disaggregated approaches to risk management are inadequate for analyzing overall risk to capital. Compliance with the stress testing requirements of the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR)[2]and Dodd-Frank Act Stress Testing (DFAST)[3]have caused institutions to realize that the proper evolution of cash flows, earnings and the level of capital require the simultaneous analysis of all risk factors; risk exposures are not additive. Banks are expected to resolve this fundamental issue as well a long list of other challenges in order to prove that their representations on capital adequacy can, in fact, be relied upon by regulators. Regulatory requirements continue to evolve and the bar of expectations appears to rise with each new round.

This paper builds off an earlier GFMI article on the regulatory basis for stress testing. It discusses the major components of a stress testing process and describes some of the challenges with which banks are contending. We will start with the foundational stress testing components of economic scenarios and cash flow modeling; build on the foundation with new business, capital consumption, income, and other risks; and finish with a discussion of capital ratios, capital planning, and outputs.

Economic Scenarios

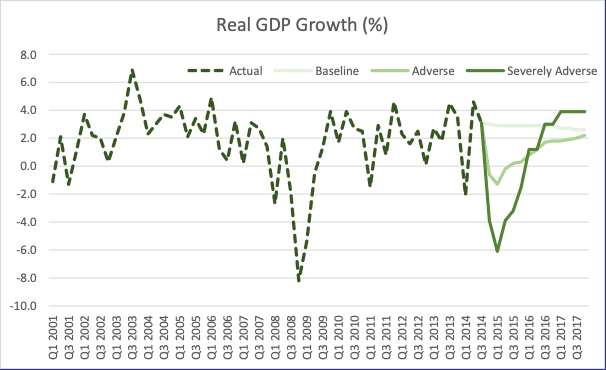

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

The starting point for CCAR and DFAST simulations is a set of economic scenarios produced by the Federal Reserve (Fed); the set consists of Baseline, Adverse, and Severely Adverse scenarios. Banks are required to produce estimates of pre-provision net revenue (PPNR) in each of these scenarios and must demonstrate that they have sufficient capital throughout the entirety of each scenario.[4]Each scenario includes 16 domestic variables and 12 international variables (three each for four regions). The Fed provides an extensive history as well as a 13-quarter forecast for each variable.[5]

While the Fed’s specification of the scenarios provides a useful starting point for forecasting, accurate forecasts require several extensions of the data set:

- Additional macroeconomic variables which have explanatory power for the performance of the bank’s lending and investing activities, e.g. oil prices

- Expansion of the national variables down to local drivers of default and loss, e.g. state-level unemployment and zip code level home price indexes (HPI)

- Extension of the forecast horizon beyond 13 quarters as necessary to meet the modeling requirements for Other Than Temporary Impairment (OTTI), e.g. rates and other macroeconomic parameters through the maturity term of the securities

In addition to the Fed’s specification of the scenarios and the extensions described above, there is an expectation (and for larger banks a requirement) that banks will supplement the scenarios in a way that acknowledges idiosyncratic risks. For example, a bank with a heavy reliance on wholesale funding should consider loss of access to certain wholesale markets, e.g. repo, CP, or FHLB market shutdown. This analysis can be included with the bank’s formal submission or made available for subsequent regulatory review. If the bank is solving for a post stress capital measure that aligns with the CCAR measure, the specification of the event should reside in a similar probability space as the Fed’s Severely Adverse scenario.

Cash Flow Models

The assessment of capital adequacy over the forecast horizon derives from the evolution of scenario-specific, transaction-level cash flows for each balance sheet position. The capital requirements for a position are a function of realized principal and interest cash flows, risk-weighted asset (RWA) levels, as well as mark-to-market levels for traded positions. Cash flows are produced from an estimate of contractual, voluntary and involuntary payments; RWA levels are assigned based on regulatory classifications; and mark-to-market levels are based on modeled values.

In most banks, the management of the analysis of credit and market risk is in separate functional areas. This segmented approach to risk management persists and is evidenced by attempts to add the impact of market and credit risk exposures in order to determine product cash flows. There is a failure to recognize that this approach will not produce cash flow dynamics that reflect their real world behavior.

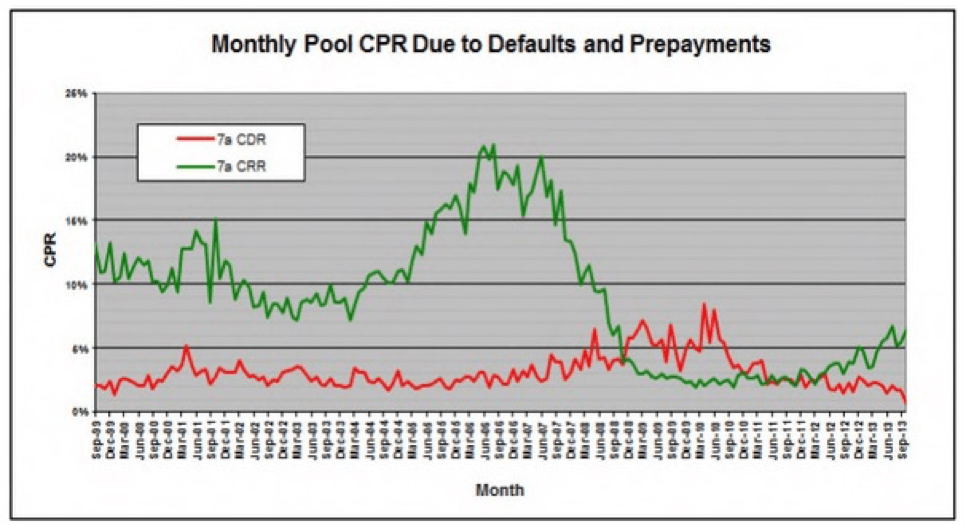

Source: Government Loans Solutions’ CPR Report |

A class of behavioral models, known as competing risk models, are best suited for the correct evolution of cash flows; such models consider, in each period of a simulation, the simultaneous impact of relevant cash flow drivers. For example, these models incorporate market risk factors, such as current interest rates on comparable products, which will explain voluntary prepayment behavior, as well as credit risk factors, such as loan-to-value (LTV), which will explain default and loss experience, but in considering them jointly, these models are also able to acknowledge that the latter factors may serve to constrain the realization of voluntary prepayments that would otherwise be expected when focusing solely on interest rates.

The requirement for this type of model is evident when we analyze the failure of loan prepayment models used before and during the recent financial crisis. In 2007-8, mortgage prepayment models predicted that voluntary prepayment rates would increase dramatically because of the substantial decline in market interest rates. The model predictions proved incorrect because housing prices were in decline at the same as rates were falling. Homeowners found that they had LTVs which exceeded underwriting limits at most banks; as a result, they were unable to refinance their loans notwithstanding their strong desire to do so. In this case, when analyzing capital adequacy in a deteriorating economic environment, prepayment models that overstate prepayment rates will understate credit exposure and capital risk thus leading to incorrect conclusions about the sufficiency of capital. Because stress testing specifically requires the consideration of comprehensive economic scenarios, cash flow models must incorporate all relevant factors that explain the evolution of cash flows.

| Table 1: Sample Loan Fields

Loan Type Origination Date Maturity Date Original Balance Current Balance Current Interest Rate Fixed/Floating Repricing Rate Index Repricing Rate Spread Prepayment Option Flag Prepayment Option Type Original Collateral Value Current Collateral Value Original FICO Score Current FICO Score Guarantor ZIP Code Current Delinquency Status Vehicle Age Vehicle Type Borrower Age Borrower Gender Borrower Income |

Individual behavioral models require development for each balance sheet product because in most cases, cash flows include not only contractual rules, but also voluntary and involuntary prepayment (or credit default and recovery) options, the structure of which varies from product to product and across collateral structures. The process for developing the behavioral model for each product must include a step in which the relevant drivers of cash flow dynamics are identified. Calibration of these models must be consistent with the performance experience of the product. This process requires the use of numerous data fields, examples of which are in Table 1. (This list is not complete, and for certain types of loans, certain fields may not be relevant.) In addition, effective model risk management[6]requires periodic back testing and recalibration of model factors.

The availability of sufficient internal loan data has proven problematic for most banks across their entire suite of products. Retention of loan level performance histories is a recent development, and may not capture the most recent credit cycle, or they may fail to capture an adequate breadth of performance attributes. Even if they have ten years of history, these data only capture a single business cycle. For this reason, many banks must utilize external data sets to calibrate their models. Initially, regulators were insistent that banks use only their data for this purpose, but have since acknowledged the benefits of using more comprehensive data sets, provided the augmented data demonstrate an appropriate fit to the business and risk profile of the organization’s existing exposures.

For securities, the following further complicates cash flow modeling:

- While the availability of loan performance data is generally limited only by the ability of banks to capture and retain the necessary data fields, for securities, most banks are reliant on external parties to provide complete and accurate time series data necessary for modeling and analysis.

- Most investment products have a waterfall structure, which governs the evolution of cash flows to the investor. While it is important to model the performance of the underlying collateral, e.g. amortization, voluntary and involuntary cash flows on individual loans within an MBS, in a manner that is consistent with the specified scenario, these transaction-level cash flows must be passed through the waterfall structure in order to accurately project the actual cash flows which will be realized over the forecast horizon.

- Given the first two points, loan level cash flows on whole loans and those in structured securities products are usually evolved in separate modeling constructs. There should be demonstrated consistency in the evolution of loan level cash flows, whether they are in whole loan form or as collateral in structured products.

With regard to reliance on third parties for securities modeling, regulators are demanding an increase in the level of transparency around the modeling process. Some third party modelers have refused to acquiesce to these demands as their models provide the proprietary base of their asset management businesses. This has left many banks searching for alternatives or attempting to develop bespoke in-house solutions.

New Business and Reinvestment of Cash Flows

Balance sheet stress testing requires the estimation of volumes, risk, income, and expenses over a multi-period horizon. The need to simulate earnings in addition to balances requires detailed assumptions around the evolution of new business and reinvestment of runoff cash flows. All of the same requirements for modeling the cash flow dynamics of the existing balance sheet apply to the new balances coming onto the balance sheet. In addition, new business assumptions should have some econometric justification, which would evolve in response to explicit business strategies.

In the same way that well-built behavioral models impose extensive data requirements on current positions, all new business will need to include the same level of specificity as these positions and should be evolved using the same cash flow models used to run off the current position balances. ALM modelers will already be familiar with the need to make explicit assumptions for new business volumes coming onto the balance sheet in each period, including details of their maturity terms, repricing terms and repricing spreads. In addition to these IRR-related variables, details around the credit characteristics of the new business will also have to be specified, e.g. FICO scores, LTVs, collateral values, etc. Because credit risk has not been within the scope of ALM modeling, this information will most likely have to source from the business units responsible for product origination.

Business units have long engaged in periodic budgeting and forecasting exercises, but they are discovering that the level of rigor used is not sufficient to meet regulatory expectations for balance sheet stress testing. The development of a budget is typically a top down exercise to support high-level growth objectives, e.g. 10% earnings growth. Simply planning to do 10% more of everything might achieve this objective; alternatively, the bank might employ strategies that emphasize specific products. Regardless, the aim of the budget is to support a top down target. Econometric models, which correlate portfolio growth or new volume originations to economic variables, are typically not used. In other words, the primary earnings objective drives the assumptions, not economic rational.

Scenarios for budgeting have also typically been described with no more underlying detail than a basic forward projection of interest rates that might not even be a forecast at all; e.g. many banks still budget under an assumption of flat rates. Budgeting and forecasting are almost never done within the context of fully specified economic scenarios. Even if there is a specification of conditions, given their relatively short-term focus, these exercises rarely include future conditions that are materially different from current ones. As a result, business units have not formally thought about the relationship between economic variables and business origination.

In contrast to these practices, regulatory stress testing requirements for forecasting reflect a strong preference for econometric models which naturally lend themselves to the study of the impact of changes in economic variables on business origination. As a result, many banks are finding that they have to increase the level of sophistication of their forecasting processes. For example, in early rounds of stress testing, banks were prone to utilize the same budget assumptions in all of the Fed scenarios, in effect saying that the budget would be achieved “come hell or high water.” Admirable though this attitude may be, regulators pushed back on this naïve approach demanding that banks understand and acknowledge the relationship between economic variables and the business they originate. This is not to say that the bank should ignore business strategies, but rather that they should fit logically within the relevant economic context. For example, if a scenario calls for housing prices to fall rapidly and economic activity to shrink significantly, a bank should anticipate a slowdown in mortgage production and related interest and fee income even if it had otherwise planned a significant increase in mortgage growth.

To be clear, there is not an expectation that banks rely entirely on the output of econometric forecast models. If strategies are currently in place that emphasize certain products, these will likely not have been captured in the predictions of historically calibrated econometric models. As such, business units should override the model output. Such overrides, even though warranted, open up the potential for criticism if they are not handled properly; regulators are prone to reject them when documentation and support are inadequate.

Regulators are also quick to reject an assumption that lending activity will be curtailed at the first sign of an economic downturn; forecasts should not assume perfect foresight. For most market participants, there was no comprehension that the crisis would be as severe as it ultimately was. Regulators have rightly concluded that growth strategies are likely to drive behavior long after risk-taking that is more prudent should prevail. Curtailment should only be assumed when credible contingency plans, e.g. those with mandatory stop losses, are in place as there is strong evidence that banks which were lending aggressively going into the previous crisis continued to do so even as housing prices began to decline and credit quality began to deteriorate.

Risk Capital Consumption Models

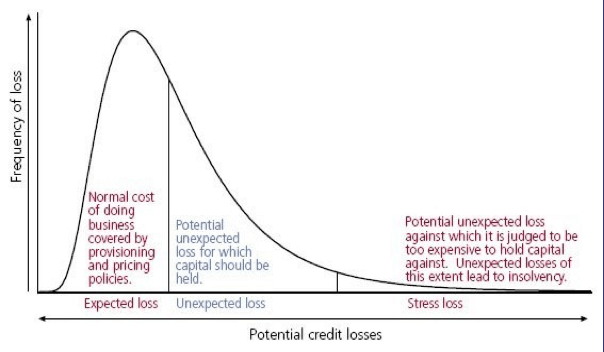

Source: Wikipedia page: Advanced IRB |

Once the evolution of the existing book and new business volume cash flows extend over the forecast horizon in each scenario, the next step is to calculate the capital consumption for each asset arising from the risk of the asset. Capital consumption occurs through both regulatory and accounting constructs. From a regulatory perspective, the different Basel regimes (I, II, III) require that individual assets be placed into risk buckets, each of which has a specific RWA charge; these charges are aggregated and total RWA must be funded with a minimum level of capital. Accounting constructs relate to the management of the Allowance for Loan and Lease Loss (ALLL) account as well as the assessment of Other Than Temporary Impairment (OTTI)[7]on investment securities. The ALLL account is a balance sheet account that is adjusted through the provision line item in the income statement; OTTI adjustments also pass through the income statement. Changes to either of these income accounts will affect the rate of capital accumulation or shrinkage. In stress scenarios, these impacts can be material; as a result, the processes a bank uses to calculate them is likely to receive a tremendous amount of regulatory scrutiny.

RWA amounts are generally determined by assigning on-balance sheet assets to broad risk-weight categories according to the counterparty, or, if applicable, the guarantor or collateral. Similarly, RWA amounts for off-balance sheet items are calculated by a two-step process: (1) multiplying the amount of the off-balance sheet exposure by a credit conversion factor (CCF) to determine a credit equivalent amount, and (2) assigning the credit equivalent amount to a relevant risk-weight category. In addition to the category, the balance and risk of the position must be determined. For performing loans, the former is simply the outstanding book balance and for defaulted loans, it is the Exposure at Default (EAD). The risk of the position is a function of default likelihood, loss profile, and maturity. It is important to recognize that many of the components of RWA calculations are similar to those needed for the measurement of ALLL and OTTI. There should be consistency between the bank’s calculation of regulatory and accounting measures of capital consumption. To the extent that they are not consistent, the bank may be subject to regulatory criticism.

RWA classifications have grown increasingly more granular with each subsequent Basel regime. Basel I classifications made some distinctions between asset types, but underlying credit characteristics and credit migration were largely ignored. The adoption of Basel II and Basel III addresses many of these weaknesses. RWA calculations now better reflect the actual risk of the position; unfortunately, the process for determining RWA levels is now significantly more complex and requires the tracking and analysis of many more data fields. These calculations have proven challenging for a number of banks as the necessary data is not readily available.

The calculation of OTTI has also proven problematic. Banks typically take very little credit risk in their investment portfolios, opting to invest primarily in sovereign or guaranteed securities; for these instruments, OTTI is a moot point. In contrast, positions with credit risk, e.g. municipal securities, non-agency MBS (NAMBS), or preferred stock, dohave credit risk. While OTTI is probably zero under base conditions for most bank-owned investment securities, this assumption is less likely to hold for stress scenarios. Regulators are frequently demanding that this assumption be substantiated with properly constructed analytical models which bifurcate value changes into those due to credit events and those due to other factors such as an increase in liquidity spreads.

In addition to the forecast of RWA, ALLL and OTTI, various other risk oriented capital consumption activities must be forecast to comply with applicable accounting and regulatory standards; for example, the unrealized loss on Available for Sale (AFS) portfolio securities which flows through Other Comprehensive Income (OCI) now counts against regulatory capital for large banks. A further modeling and reporting challenge arises as some of the new limits and revisions to existing limits will phase in over the next several years.

Additional Risk Exposures

In addition to credit risk, there are additional drivers of loss and capital consumption that the stress testing process should address; these include liquidity risk, operational risk, counterparty risk, and trade book risk. These exposures tend to be highly idiosyncratic and the Fed scenarios do not specifically address them. Even so, banks should acknowledge and incorporate them into the stress testing exercise. The complexities of incorporating these measures include differences in measurement time horizon (liquidity and trade book events are typically very short-lived in relation to the nine quarter stress testing horizon) and low correlations with macroeconomic drivers (operational risk events, counterparty defaults and liquidity crises are exceptionally rare).

An example of an idiosyncratic risk is the exposure to liquidity risk that occurs through a heavy reliance on wholesale sources of funding, e.g. FHLB advances, commercial paper, or brokered deposits. During the most recent crisis, troubled banks lost access to some or all of these sources of funds and increased deposit rates to attract necessary funding. These actions further reduced earnings and capital accumulation. Another example would be the large Wall Street investment banks which have significant counterparty exposures which occur through a multiplicity of products, e.g. credit default swaps (CDS), interest rate swaps, and back-up lines of credit (LOCs). Banks should analyze the impact of similar types of events. These can be constructed and analyzed in separate scenarios or incorporated directly into the Fed stress scenarios.

Operational risk poses many unique challenges when considered in CCAR type stress scenarios. Both realized losses and RWA consumption would affect capital ratios. This is similar to credit risk with RWA and charge offs, but is made more complicated by the difficulties associated with tying macroeconomic scenarios to event outcomes that lack correlation with the scenario. Generally, banks should consider evolution of their operational risk losses with those categories that have a relationship to higher loss profiles in other activities. For example, process failures in environmental assessments will only become evident in times of high real estate foreclosure, so a scenario could be built addressing that (potential) relationship.

Income and Expense Models

In a previous section, we addressed some of the challenges associated with forecasting new business volumes and cash flow dynamics on these and existing balances in credit stress tests. Because the objective of the exercise is to calculate capital ratios, the capital supply needs an assessment of the net income (or loss) for each period in the forecast. Most institutions turn to their ALM model given the long standing tradition of modeling the cash flows that lead to income under stress, although typically only in rate-driven scenarios. In analyzing IRR, most institutions focus on the net interest margin (NIM), which is simply the difference between interest income and interest expense. Some banks calculate only this measure of earnings in their analysis as it captures the majority of earnings volatility associated with changes in the level of market interest rates. For CCAR stress testing, banks must calculate net income (NI) and incorporate dividend and stock buy-backs to estimate capital accumulation.[8]In the former case, non-interest income and expenses are not addressed at all, as they do not affect the calculation of NIM. In the latter case, though, the bank may specify the level of non-interest income and expense, but it is common practice to assume that these line items are not rate sensitive. Because the point of the IRR exercise is to understand how changes in interest rates will affect earnings and economic capital, additional risk factors remain unchanged to keep the analysis pure. We have already noted that traditional budgeting and forecasting exercises assume business as usual across a very short time horizon. This means many banks are likely to find that internal models of non-interest income and expense dynamics are very simple, if they exist at all, and do not meet the needs of credit stress testing.

Examples of non-interest income and expense dynamics which would need to be well-understood include the level of mortgage origination fees in a slow housing market, foreclosure and asset maintenance expenses associated with an increase in unemployment, incentive compensation levels when capital levels are stressed, marketing expenses associated with raising additional retail deposits to offset loss of other funding sources, legal expenses in a housing crisis, and investment banking and legal expenses associated with efforts to raise capital.

In addition to the core issues around the calculations themselves, cash flow should be consistent across balance sheet (position balances) and income statement measures for those positions across interest and non-interest income (income and expense from interest, fees, and provisions). Positions that are no longer on the balance sheet because of credit impairment (through charge offs) should also be excluded from income calculations. This is difficult for banks that perform these calculations in systems with different charts of accounts (ALM chart of accounts based on rate criteria often do not typically line up with credit pools that use geography, leverage, and cash flow). The manual processes associated with spreading the impacts from one chart of accounts (credit) over a different criteria (ALM) will introduce inconsistencies and decrease speed and flexibility needed as scenarios and impacts evolve.

Capital Ratio Calculations

A variety of regulatory and accounting measures of assets and capital are part of the definition of the different capital ratios for which minimum levels have been set. These ratios take the following form:

The capital measure in the above equation corresponds to a capital supply measure; these include Common Equity Tier 1, Tier 1 Common, Tier 1, and Total Capital. The asset measure in the calculation can be either risk-weighted or volume weighted (for simple leverage measures).

Source: Bank for International Settlements |

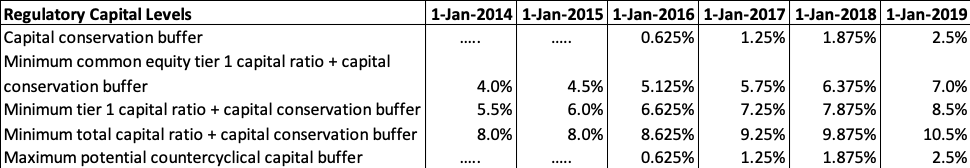

In 2012, US bank regulators issued their final rule for implementation of the Basel III capital standards.[9]The rule revises their risk-based and leverage capital requirements and implements a revised definition of regulatory capital, a new common equity tier 1 minimum capital requirement, a higher minimum tier 1 capital requirement, and, for banking organizations subject to the advanced approaches risk-based capital rules, a supplementary leverage ratio that incorporates a broader set of exposures in the denominator. The rule also incorporates these new requirements into the agencies’ prompt corrective action (PCA) framework. In addition, the final rule establishes limits on a banking organization’s capital distributions and certain discretionary bonus payments if the banking organization does not hold a specified amount of common equity tier 1 capital in addition to the amount necessary to meet its minimum risk-based capital requirements. Further, the final rule amends the methodologies for determining risk-weighted assets for all banking organizations and introduces disclosure requirements that would apply to top-tier banking organizations domiciled in the United States with $50 billion or more in total assets. It also adopts changes to the agencies’ regulatory capital requirements that meet the requirements of section 171[10]and section 939A[11]of the DFA.

While all CCAR and DFAST banks are expected to demonstrate compliance with the minimum capital ratios in all of the stress testing scenarios, the Fed actually runs its own stress testing model for each of the CCAR banks in order to independently assess capital adequacy. It is these model results, not the bank’s own, which determine if the bank passes or fails the stress testing exercise. This raises a huge challenge for CCAR banks, as there is the possibility of material differences between their internal models and those of the Fed. For example, banks with large wealth management units find that their own loan loss projections are significantly less than the Fed’s, even when these projections are consistent with their loss experience. This can lead to the need for capital buffers for the Fed scenario beyond what the bank needs for their internal application of the stress test.

Because some of the new capital requirements were anticipated to force banks to accumulate or issue significant amounts of new capital, banks are being allowed to phase-in compliance with the new minimums over the next several years. A bank may therefore find itself, within the forecast horizon of the stress test, dealing with a change in the applicable Basel regime as well as the phase-ins. This makes the task of demonstrating compliance with the minimum requirements a challenging process. Also included in the new guidance are phase-outs of certain types of capital which banks were previously allowed to count toward regulatory capital, e.g. trust preferred securities. Correct modeling of these phase-outs facilitates a determination of projected needs for raising alternative forms of capital.

Capital Planning

The production and consumption of capital includes the net income, accounting, and RWA effects outlined previously. In addition, core to CCAR and DFA stress testing is the principle that capital should be adequate today to meet the challenges of a stress environment and that capital actions contemplated in the plan would not jeopardize the bank in a stress environment. Traditional capital activities, including dividends, share repurchases, the issuance of various capital instruments, and merger activities should contemplate not only the consumption of capital within a base environment, but also the amount of capital needed for the volatility of the bank’s capital activities under stress.

There are four mandatory elements of the capital plan:

- An assessment of expected uses and sources of capital

- A detailed description of the BHCs process for assessing capital adequacy

- The BHC’s capital policy and

- A discussion of any baseline changes to the BHC’s business plan that are likely to have a material impact on the BHC’s capital or liquidity adequacy.

Each of the mandatory elements should contemplate base and stress conditions for both the current position, as well as over a forecast horizon. The forecast may need to extend beyond the 13 quarter CCAR horizon in cases where regulatory phase-ins and other business activities may materially influence the capital position of the bank. While preceding sections deal with the calculation of the capital consumption of the various core business activities of the bank, there are additional considerations for the capital activities of the bank.

Dividends

There is a regulatory view that dividends are difficult to reduce or suspend in stress environments. Realistically, banks would be very hesitant to reduce or eliminate dividends without similar consistent and systemic actions across the peer group. Because of this view, there is a soft cap on the percentage of dividends paid out of earnings of 30%. While it is possible for banks to pay out more than 30%, such requests would face a higher level of scrutiny and be difficult to justify as a regular business practice. Dividends include common and preferred shares. In addition to dividends paid to public markets, support for dividends between US regulated entities and non-US regulated legal entities should be in the capital plan.

Share Repurchases

There are a variety of different repurchase programs that a bank can contemplate. Some are bank directed, and are easier to start or curtail. Others are difficult for the bank to modify once commenced. In all cases, the bank should specify criteria for what types of market and economic conditions would lead to suspension (or non-execution) of the program. Any program should also differentiate the portion of repurchases needed to support compensation related share purchases from pure market activities as the compensation related shares will end up back in the market. Both dividends and share repurchase programs will require a forecast of share price to allow volumes and impacts to be accurately calculated.

M&A

Rarely would a bank know the specific target of contemplated acquisitions well in advance of the execution of the activity. Lacking a specific target, the question requiring discussion is what capital reserve will handle various sizes of potential activity without the need to modify other uses of capital (such as share repurchases or dividends). At what size of activity would the bank need to re-submit and/or re-build their stress test and capital plan? What types of acquisitions would represent a material change to the bank’s business model regardless of size? Portfolio acquisition or divestitures, if material, would require analysis in a similar fashion to broader M&A activity.

Quantitative Output

The FRY-14 and DFAST Schedules required for submission are both detailed and holistic across all of the activities of the bank. They include both current positions as well as forecast data. The skill set needed for the production of these schedules bridges financial planning, accounting, and risk activities with few organizations equipped with the cross functional teams needed for the production of these schedules. In addition, the use of the schedules is not typically a business-as-usual activity of the bank. As such, they are not afforded the opportunity of review by those “closest to the numbers” that would be typical for normal bank forecasting activities. The amount of detail needed with the schedules also creates issues for the bank. Pre-Provision Net Revenue (PPNR) schedules are often at a level of detail and/or definitional classification that create difficulties for both direct modeling as well as for consistency across disparate processes for income and balance sheet modeling.

The combination of required detail, limited internal use, and application across existing bank experience silos creates a higher risk of inaccuracy once submitted. The schedules are an area where internal review functions will need to spend time and resources. Clearly waiting until the last minute to complete the production of these schedules would make the review of these schedules difficult and of limited value.

Qualitative Elements

Recent results from the CCAR process show banks passing the quantitative aspects of the stress process, but some are failing for qualitative reasons. While there are likely a variety of contributing factors, failure to apply a validated and transparent modeling framework and limited integration of stress testing in core bank activities seem to be dominant themes. Existing processes including Risk Identification, Risk Appetite, Strategic Planning and Budgeting, and Risk Measurement and Forecast should include stress testing concepts, but also serve as core inputs to the CCAR/DFA stress testing process. In addition, many banks have discovered that merely putting models in place to calculate numbers is not enough. There needs to be an understanding of the power and limitations of the various modeling approaches, and adequate transparency of the employed models to allow management and the board to understand the level of confidence appropriate for the chosen approaches.

Each element needed in CCAR/DFA stress testing both relates to and depends on the other elements involved in the process. A successful program should be carefully constructed with thoughtful model selection, extensive education and training, strong validation and challenge, and appropriate integration with existing bank processes. With this approach, CCAR/DFA stress testing can serve as both a regulatory compliance exercise as well as a core business planning activity that allows the bank to make smarter decisions.

Conclusion

The stress in stress testing for banks comes from both the difficulties in calculating each of the individual components consistent with the scenario as well as the need to have consistent application of the scenario across the components. All of the required forecasts and supporting elements are remarkable in their breadth and their detail. All of this work is done against firm submission deadlines, with severe consequences for either missing a calculation component or demonstrating a deficiency in approach in relation to peers. While we may never fully take the stress out of stress testing, we hope that having an end-to-end understanding of what the process entails will at least help in understanding the nature of the problem and gets the team aligned with the right objectives. After all:

“Suffering becomes beautiful when anyone bears great calamities with cheerfulness, not through insensibility but through greatness of mind.”– Aristotle

About the author

Jim Haught brings almost 30 years of risk, capital, and training experience with extensive knowledge of modeling, forecasting, and risk measurement. Currently, Jim is a Managing Partner of the Exequor Group (www.exequorgroup.com). Exequor is a consulting practice with focus areas in modeling and risk management in the Financial Services and Life Sciences industries. Jim built the Financial Services practice, and serves as the firm expert in Comprehensive Capital Assessment and Review (CCAR) and Dodd-Frank Act Stress Testing (DFAST). In his advisory capacity, Jim built stress testing and capital planning training programs, and works with banking clients to assist them with governance, documentation, model development and validation, and program management for risk and treasury initiatives. Beyond his responsibilities with Exequor, Jim serves as the President of CogForma Labs (CFL). CFL builds and deploys behavioral cash flow models for use in forecasting bank asset contractual, prepayment, and credit related cash flows in support of stress testing efforts.

Jim Haught brings almost 30 years of risk, capital, and training experience with extensive knowledge of modeling, forecasting, and risk measurement. Currently, Jim is a Managing Partner of the Exequor Group (www.exequorgroup.com). Exequor is a consulting practice with focus areas in modeling and risk management in the Financial Services and Life Sciences industries. Jim built the Financial Services practice, and serves as the firm expert in Comprehensive Capital Assessment and Review (CCAR) and Dodd-Frank Act Stress Testing (DFAST). In his advisory capacity, Jim built stress testing and capital planning training programs, and works with banking clients to assist them with governance, documentation, model development and validation, and program management for risk and treasury initiatives. Beyond his responsibilities with Exequor, Jim serves as the President of CogForma Labs (CFL). CFL builds and deploys behavioral cash flow models for use in forecasting bank asset contractual, prepayment, and credit related cash flows in support of stress testing efforts.

Before becoming a consultant, Jim was the Global Head of Capital at State Street with responsibilities that included coordinating the CCAR submission, producing the Capital Plan, designing and running the ICAAP for the organization, building the risk adjusted performance framework for the lines of business, and leading all capital actions. Mr. Haught is well experienced with all Basel regimes, Economic Capital and stress testing including the forecasting of those measures.

Prior to joining State Street, he served in various risk and capital positions at RBS Citizens, including leading quantitative teams responsible for credit modeling and pricing, implementing the bank’s ALM model, building the commercial rating framework, and designing and implementing the initial Basel II advanced models for credit risk measurement. Jim began his career at RBS Citizens as a commercial lender, but was drawn into risk through his fascination with risk-adjusted returns.

Mr. Haught began his career as a Surface Warfare Officer in the United States Navy. While in the Navy, Mr. Haught spent his last years before his leaving the service as a Gas Turbine Engineering trainer in Newport, RI. During this tour, he was designated as a Master Training Specialist. Jim has a BA from the University of Rochester, and he received his MBA from the University of Rhode Island. Jim is a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA), a Financial Risk Manager (FRM), and a Professional Risk Manager (PRM).

Copyright © 2015 by Global Financial Markets Institute, Inc.

[1]These include non-public requests for remediation, such as matters requiring attention (MRA) and matters requiring immediate attention (MRIA) as well as explicit restrictions on the payment of dividends to shareholders and prohibitions on stock buybacks.

[2]Applicable to bank holding companies (BHCs) with total assets over $50 bln.

[3]Applicable to bank holding companies with total assets between $10 bln and $50 bln.

[4]Minimum capital levels are specified for several metrics: Tier 1 Common, Common Equity Tier 1, Tier 1 Risk-Based Capital, Total Risk-Based Capital and Tier 1 Leverage. Minimums have also been separately specified for Advanced Approach BHCs versus other BHCs and are being phased in through 2019. See www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/bcreg20150311a1.pdffor complete details.

[5]Complete histories are provided for each variable back to 1999; additional history is provided for a subset of the variables as far back as 1976 with forecasts designed for nine quarters with an additional four quarters to demonstrate reserve adequacy at the conclusion of the nine quarters

[6]See OCC 2011-12 or SR 11-7 Model Risk Management for the regulatory requirements around effective model governance.

[7]OTTI refers to the change in the value of a security that is attributed to an expected credit event, e.g. loss of cash flow to the investor due to mortgage defaults in an MBS. This impairment is treated differently that a loss of value that is attributed to an increase in market interest rates or liquidity spreads.

[8]In high rate environments, this can be quite important because equity acts as a free source of funding. Strong earnings growth therefore can mitigate liability sensitivity.

[9]See OCC 2012-0008.

[10]This section requires regulators to establish minimum leverage capital and risk-based capital requirements for insured depository institutions, depository institution holding companies, and nonbank financial companies supervised by the BOG. In addition, it establishes that certain BHC subsidiaries of foreign banking organizations which were exempt from the minimum capital standards must now comply with the standards via a phase-in process.

[11]This section prohibits banks from relying on rating agency risk measures, e.g. Moody’s and S&P ratings, for estimated risk exposures; alternative methods must be developed.

Download article My Cart

My Cart