What is ESG?

The acronym “ESG” stands for environmental, social, and governance. More importantly, the term ESG has become synonymous with the concept of “sustainability.” In the capital markets, ESG criteria are a set of standards that should help to assess an organization’s operations evaluate potential investments in securities issued by those organizations. The universe of issuers includes corporations, sovereign issuers such as local or national governments, and supra-national organizations like the World Bank.

- Environmental criteria assess how an issuer safeguards the environment, including internal policies addressing climate change, for example.

- Social criteria assess how an issuer manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates.

- Governance deals with an issuer’s leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights (if the issuer is a corporation).

The term ESG was first popularized in 2004 in the UN Global Compact’s report Who Cares Wins1, which outlined recommendations by a consortium of financial institutions to “better integrate environmental, social and governance issues in analysis, asset management and securities brokerage.” The report noted that “the industry [had] not developed a common understanding on ways to improve the integration of ESG aspects in asset management, securities brokerage services and the associated buy-side and sell-side research functions,” and stated that greater inclusion of ESG factors in investment decisions would “contribute to more stable and predictable markets.”

The UN’s Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI) was also formed in 2004. The PRI is a United Nations-supported international network of investors working together to implement its six principles. Its goal is to understand the implications of sustainability for investors and support signatories in incorporating these issues into their investment decision-making and ownership practices. In implementing these principles, signatories contribute to the development of a more sustainable global financial system.

As of March 2022, more than 4,800 signatories from over 80 countries representing approximately US $100 trillion have become PRI signatories. In some cases, before retaining an investment manager, institutional investors will ask for evidence that an asset manager is a signatory, making PRI signatory status a kind of “gold standard” in the industry.

The six Principles for Responsible Investment offer a menu of practices for incorporating ESG issues into investment strategies:

ESG covers a broad range of sustainability factors. However, given the increased attention being paid to climate risk around the globe, the focus of ESG investing has traditionally been on the environmental (“E”) component. As a result, The G-20 Financial Stability Board (FSB) established the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in 2015 to develop recommendations for more effective climate-related disclosures from issuers that:

- could “promote more informed investment, credit, and insurance underwriting decisions” and,

- in turn, “would enable stakeholders to understand better the concentrations of carbon-related assets in the financial sector and the financial system’s exposures to climate-related risks.”

Companies and asset managers that adopt the TCFD framework are expected to provide robust disclosures in four major areas:

TCFD Framework

Governance – The organization’s governance around climate-related risks and opportunities

Strategy – The actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organization’s businesses, strategy, and financial planning

Risk Management – The processes used by the organization to identify, assess, and manage climate-related risks

Many investors are requiring ESG disclosures from issuers that adhere to the TCFD framework to ensure that sustainability data are reported in a relatively standardized format. This enhances the transparency and comparability of ESG data among issuers.

Examples of ESG-Aligned Investments

Many investors are seeking to deploy their capital into investments that have environmental sustainability, positive social impact, and strong governance factors. Many investment management firms offer funds and strategies that claim to have these desirable characteristics. But what does an ESG-aligned investment look like?

Some securities have obvious ESG characteristics. These are usually securities that are issued to provide funds for projects that have positive environmental or social impacts.

Green Bonds

Green bonds are generally issued to have a positive environmental impact. Historically, the largest issuers of green bonds have been supra-nationals such as the European Investment Bank (EIB), World Bank Group (WBG), and International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private sector division of WBG. However, corporations are increasingly issuing green bonds to fund projects like the construction of renewable energy power generation plants or facilities with energy efficient amenities.

Social Bonds

Social bonds are generally issued to achieve certain socially desirable outcomes. For example, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have both established programs to provide financing for affordable residential and commercial housing projects. Other companies have issued social bonds to fund the construction of health care or medical facilities. There are also many public and private initiatives to issue securities to raise capital for small business formation which provide funding for small-to-medium sized enterprises (SMEs).

Sustainability-Linked Bonds

Some corporate issuers have recently begun issuing securities that are designed to provide funds for sustainable (green or social) projects, while at the same time having structural features that provide strong incentives to direct these funds to specific projects instead of being used for general corporate purposes. An example of a sustainability-linked bond would be a bond with an interest rate that would ratchet upwards by a certain pre-determined amount if certain sustainable key performance indicators (KPIs) associated with a funded project are not met. The performance of these bonds has to be monitored over time to ensure that the funds are being deployed into sustainable projects appropriately, and there is usually a formal validation process to measure conformance with the terms of the security.

Labeled vs. Unlabeled ESG Investments

Many issuers seek to have some kind of credentials attesting to the ESG alignment of the securities they issue, primarily in an attempt to attract more investors and achieve a more effective cost of capital to finance the positive environmental or social initiatives they are trying to fund. For example, many issuers of green and social bonds have aligned the terms of their securities with the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) Green, Social or Sustainable Bond Principles. These Principles provide a framework that give investors transparency into how the proceeds of these securities are being deployed. Issuers generally also seek an attestation in the form of a Second Party Opinion (SPO) from an organization that can validate the issuer’s conformance with the Principles. This provides a degree of assurance to investors that their capital is being used for the specific purposes for which the securities were issued.

Securities that are issued in alignment with sustainable frameworks like the ICMA Principles are generally called “ESG labeled” investments. Some companies also issue securities that they self-designate as being “social” or “green” without attempting to conform with any specific set of external requirements. Investors tend to view these self-designated investments with more skepticism than those issued under established sustainability frameworks like the ICMA Principles for obvious reasons.

There are also many examples of investments that have positive environmental or social impacts that do not have any formal “green” or “social” designations, which are generally referred to as “unlabeled.” An example of an unlabeled ESG-aligned investment security would be the equity shares issued by a manufacturer of solar panels. Many state and local municipalities also issue bonds that have positive social or green outcomes such as the construction of a hospital or recycling facility. Investors should conduct rigorous due diligence to ensure that any proceeds from the issuance of unlabeled ESG bonds are, in fact, being used for their stated purpose.

Some investment securities might initially appear to be unaligned with positive social or environmental impacts but are nevertheless helping to create desirable outcomes. A good example would be an investment in the equity or debt securities of an oil company. While the extraction, refinement, and transportation of any fossil fuel is clearly a major contribution to carbon emissions and climate risk, many oil companies are among the largest investors in technologies to transition to a reliance on renewable energy sources in the future. Denying these types of companies access to capital would create “stranded assets” which results in the destruction of value. Many investors are actively engaging with companies that are significant carbon emitters to help them transition to a more sustainable business model. It’s clear that each investor has to determine individually as to what they consider to be an ESG-aligned investment.

EU Regulatory Guidance for ESG

While many investors have already defined how they determine ESG alignment, many other providers of capital are looking for guidance from regulators to help sort out the vast array of investment opportunities in ESG. Historically, European governments and investors have been more concerned about climate-related issues than in the US, and consequently the development of regulatory guidance in European capital markets that reflects these concerns began being implemented decades ago. The regulatory landscape related to climate risk in Europe has evolved substantially over time and is very broad-based. However, there are two recently implemented regulations in the European Union (EU) that are the most impactful for ESG investors:

- The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) requires all financial market participants in the EU, including asset managers, to disclose on ESG issues. The SFDR seeks to limit the risk of “greenwashing” within investment strategies while increasing transparency, making it easier for investors to understand how ESG and sustainability factor into their investments.

- “Greenwashing” is the practice of trying to create the impression that a company or investment strategy is doing more to promote sustainability than it really is, often for public relations reasons.

- The Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD) significantly expands the scope of mandatory sustainability disclosures by issuers of securities. Financial and non-financial companies that fall under the scope of the NFRD must disclose information on how and to what extent their operations are associated with environmentally sustainable economic activities (Note: Since this regulation mostly impacts issuers, not investors, we’ll discuss this in a later article).

Investment funds or strategies promoted in the EU by asset managers must align with the requirements of the SFDR’s classification system, which creates three major categories of investment strategies:

- Article 6: Funds without a sustainability scope

- Article 8: Funds that promote environmental or social characteristics (“light green” designation)

- Article 9: Funds that have sustainable investment as their objective (“dark green” designation)

ESG Investing in the US

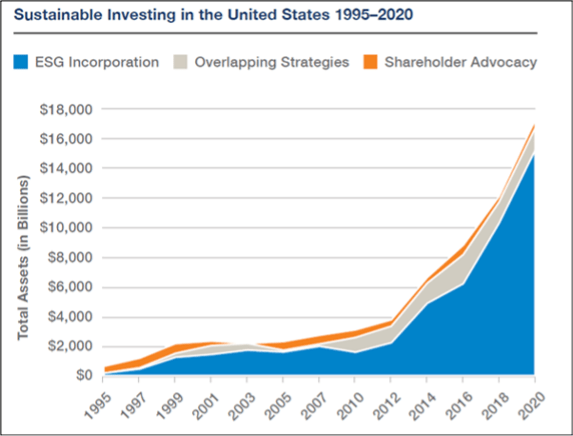

After a slow start, investors in the US have been deploying capital into ESG investment strategies at an accelerating rate, as indicated by the chart below:

Although the US SIF has not published data from 2021, other sources2 have indicated that this trend continued throughout the COVID pandemic. The chart above measures investments that align with the following categories established by US SIF:

- ESG Incorporation: $16.6 trillion in US-domiciled assets at the beginning of 2020 held by 530 institutional investors, 384 money managers and 1,204 community investment institutions that apply various ESG criteria in their investment analysis and portfolio selection.

- Shareholder Advocacy: $2.0 trillion in US-domiciled assets at the beginning of 2020 held by 205 institutional investors or money managers that filed shareholder resolutions on ESG issues at publicly traded companies from 2018 through 2020.

In 2021 the Investment Company Institute (ICI) published a taxonomy that provides clarity around the terminology that should be used by asset managers when describing ESG-aligned or sustainable investment strategies. These have been widely adopted as a market standard, and comprise the following categories:

- ESG integration: Incorporating ESG considerations into an investment process along with other material factors and analysis. This approach seeks to enhance a fund’s financial performance by analyzing material ESG considerations along with other material risks such as credit risk and counterparty risk.

- ESG exclusionary investing: Excluding companies or sectors that do not meet certain sustainability criteria or do not align with investors’ objectives. For example, a fund may not invest in companies that have significant business related to weapons manufacturing or distribution, gambling, tobacco, alcohol, or nuclear energy.

- ESG inclusionary investing: Seeking positive sustainability-related outcomes by pursuing and focusing on portfolios that fundamentally or systematically tilt a portfolio based on ESG factors alongside financial return. For example, a fund may invest in equity securities of companies that contribute to and benefit from clean energy generation, sustainable infrastructure, waste management, and other environmentally friendly approaches.

- Impact investing: Generating positive, measurable, and reportable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. Measurement, management, and reporting of impact is a defining feature of impact investing. For example, a fund may invest most of its assets in securities whose use of proceeds, in the fund manager’s opinion, provide measurable positive social or environmental benefits.

Source: ICI Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Working Group: Funds’ Use of ESG Integration and Sustainable Investing Strategies: An Introduction

US Regulatory Guidance for ESG

The US has always had a more hands off laissez faire (“leave it be”) approach to regulating financial markets compared with the EU, which has generally adopted a more proscriptive approach. The ICI’s taxonomy has been a useful tool for both issuers and investors, but many capital markets participants have been waiting eagerly for more formal guidance from the SEC and other federal regulators.

On March 21, 2022, the SEC issued for comment a proposed rule that would enhance and standardize the climate-related disclosures provided by public companies. Under the proposed rule, a publicly registered issuer would be required to provide disclosures about greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, certain financial statement disclosures, and qualitative and governance disclosures within its registration statements and annual reports (e.g., Form 10-K). We’ll dive into this proposed rulemaking more deeply in a future article addressing ESG for issuers of securities (versus this article which is addressing investors).

On May 25, 2022 the SEC issued for comment a proposed rulemaking to discuss potential regulatory guidance for investment managers who promote funds or strategies that claim to be ESG-aligned. The issues addressed by the proposed rulemaking include:

- Whether to propose amendments to the SEC’s Names Rule under the Investment Company Act that addresses investment company names that are likely to mislead investors about an investment company’s investments and risks. The amendments the SEC will consider include enhanced prospectus disclosure requirements for terminology used in investment company names, as well as public reporting regarding compliance with the new names-related requirements.

- Whether to propose amendments to rules and reporting forms for registered entities to provide standardized ESG disclosure to investors and the SEC.

Summary

In summary, investors around the globe are clearly seeking to deploy capital into securities and investment strategies that have desirable social and environmental impacts. The volume of ESG-aligned investments is currently in the trillions of dollars and is only expected to increase. Some of these investment instruments and strategies create the opportunity for investors to have an impact in specific areas where they might wish to have a very targeted impact, while others are intended to have a broader impact on reducing carbon emissions, improving society as a whole, and ensuring good governance practices among organizations that are issuing these securities. While the opportunity to have positive impact is a very desirable outcome, investors should nevertheless conduct robust due diligence into any investment instrument or strategy that is formally or informally designated as ESG aligned.

References

2 ESG funds set a new record inflow by doubling in 2021(https://www.gobyinc.com/esg-funds-new-record-inflow-2021/)

About the Author: Rob McDonough

Rob McDonough is the Director of ESG and Regulatory Initiatives at Angel Oak Capital Advisors, LLC and leads the ESG integration process across the firm’s investment strategies and corporate initiatives. He manages several company-wide projects including the firm’s commitments under the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative and the UN’s Principles for Responsible Investment. He also coordinates a variety of research and publication activities with a focus on developments in the regulatory environment for financial institutions of all types. Rob is a founding member of Angel Oak’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Committee and the Community Relations Committee.

He previously led Angel Oak’s financial institution consulting practice, where he managed client engagements which included risk model validations, strategic and regulatory stress testing implementations, and investment portfolio risk and performance assessments. Rob was Angel Oak’s Chief Risk Officer from 2012-2014 and initiated the organization’s enterprise-wide risk management framework and SEC compliance program. He also served in the Federal Reserve System for 12 years, first as an Economic Analyst in the Research Division and later as a Capital Markets Examiner in Supervision and Regulation.

Rob is a charter member of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI) Structured Products Advisory Committee, the Structured Finance Association’s ESG Task Force Steering Committee, and chairs the Fixed Income Investor Network’s (FIIN) ESG Task Force.

Rob earned an MBA with a dual major in Finance and Economics from Georgia State University and a BBA from Emory University.

Copyright © 2022 by Global Financial Markets Institute, Inc.

23 Maytime Court

Jericho, NY 11753

+1 516 935 0923

www.GFMI.com

My Cart

My Cart